The Cap Rates Are Too Damn Low

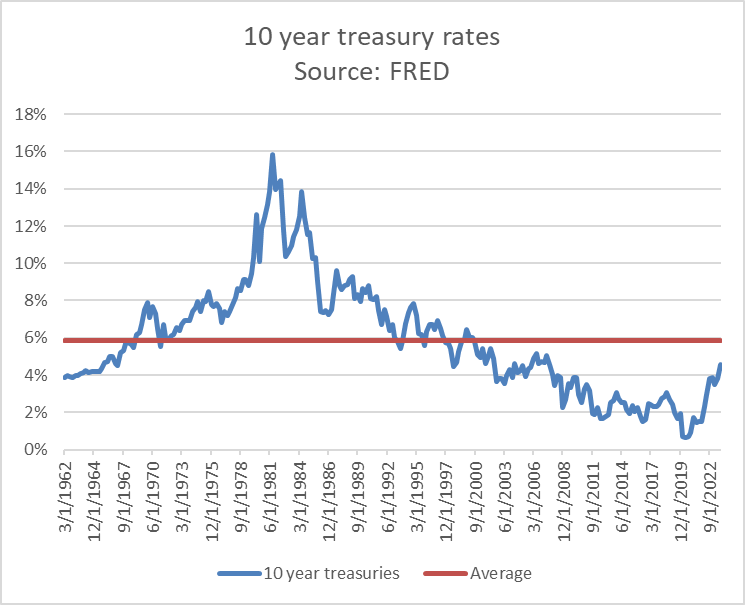

Interest rates experienced a sharp secular decline from ~1981 to ~2020. This encompasses the entire working life of most investors still active today, as well as the working lives of our teachers, mentors and bosses. It isn’t just forgotten—most of us never experienced it at all.

The last time interest rates were even at their 60 year average was in 1998.

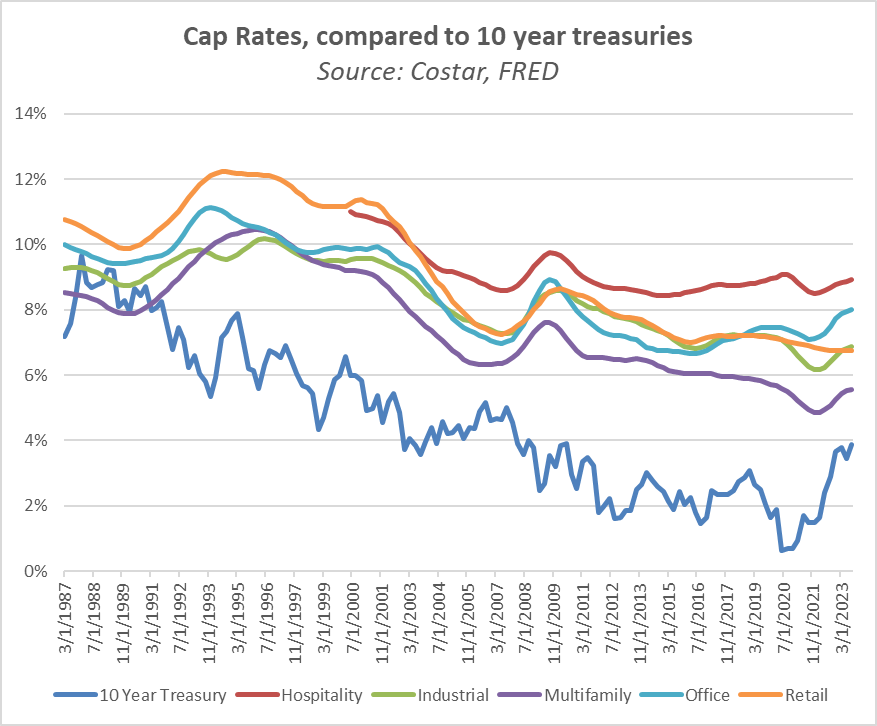

Costar has national cap rate data from 1987. Cap rates have been secularly declining, along with treasuries.

This makes sense: mortgage rates will generally be at least 150 bps higher than treasury rates so that lenders can make money, and cap rates need to be higher than mortgage rates so that owners can make money. So we should expect them to correlate.

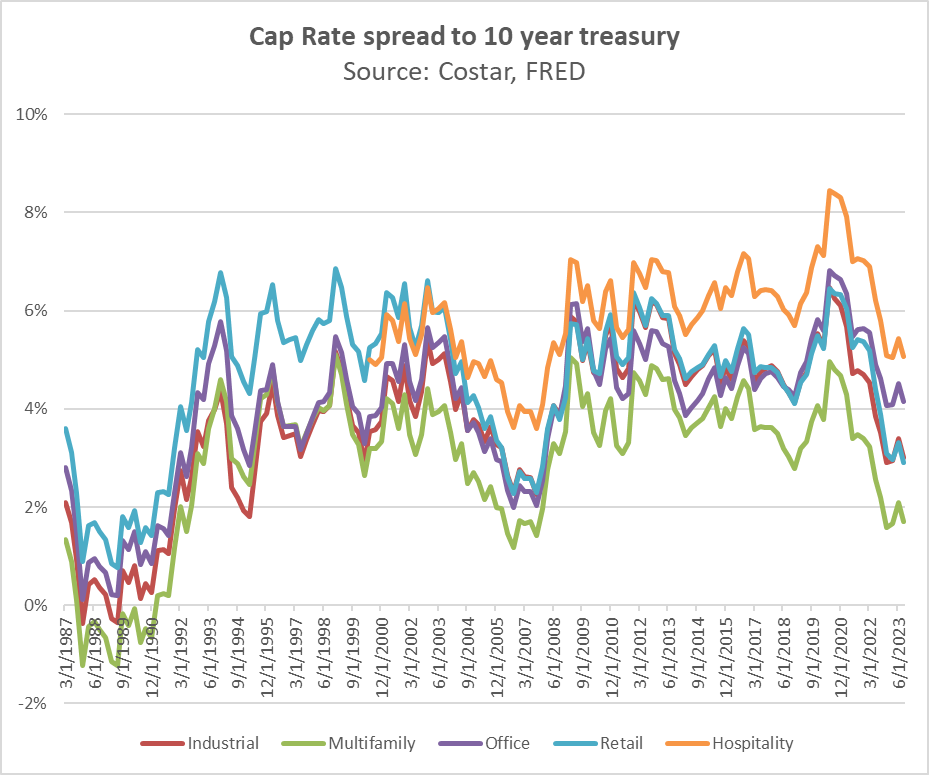

The point is more striking if we just look at the cap rate spread, which is calculated by subtracting the treasury rate from the cap rate:

The last time the spread was this low was in 2007. I see no reason to anticipate a 2008-style crisis, but it is not a reassuring comparison.

It is true that spreads were zero (or even negative) in the late 1980s, but I do not think this is a realistic analogue. This was shortly after the 1986 Tax Reform Act, which reshaped the entire real estate industry. By the early 1990s, the S&L crisis was in full bloom, and Sam Zell was giving out “stayin’ alive til 95” gag gifts. Again, not an auspicious comparison.

Preparing for distress

As the Man said, we should be greedy when others are fearful, and fearful when others are greedy.

To make a sweeping generalization, the world was fearful from 2008-2012, rationally optimistic from 2013-2019, and greedy from 2020 until now.

I’m not sure when the world will get scared, but I would not be surprised if it happens soon—and with shocking speed.

Humans are prone to loss aversion. This means that asset owners in 2023 are reluctant to sell at cap rates which are higher than 2021 levels, let alone absolute prices which are lower than 2021.

Furthermore, many owners—including myself—believe that inflation will continue to drive rents up, which is another reason not to sell at today’s prices.

Additionally, some owners expect interest rates (and hence cap rates) to decline in the future. If this proves accurate, now would be a terrible time to sell.

However at some point, owners may not have a choice. Many who took on uncapped floating rate debt are between a rock (cash-in refi) and a hard place (selling at a loss). Those who took on fixed rate debt are in a better position, but if their loan becomes due in 2023-2024, it amounts to the same thing.

If we reach the point where there are a large number of forced sellers, we could see a sharp and painful collapse of asset prices.

Practical implications

There are a few things investors can do to prepare for potential distress:

Maintain dry powder. Cash is king in a crisis.

Keep looking. In my own market (Columbus), I am starting to see a handful of fairly priced deals, even of most are still too expensive.

Use long-term, fixed rate debt. Personally, I prefer 10 years, but some LPs may balk at this. If a deal is cash flowing with this kind of debt, there are multiple ways to win:

Expanding cash-on-cash yields, as inflation drives rents & NOI up vs. fixed debt costs

Acceptable returns if rates remain high throughout the hold period

Excellent returns if interest rates & cap rates decline

Won’t the Fed bail us out? The Fed always bails us out.

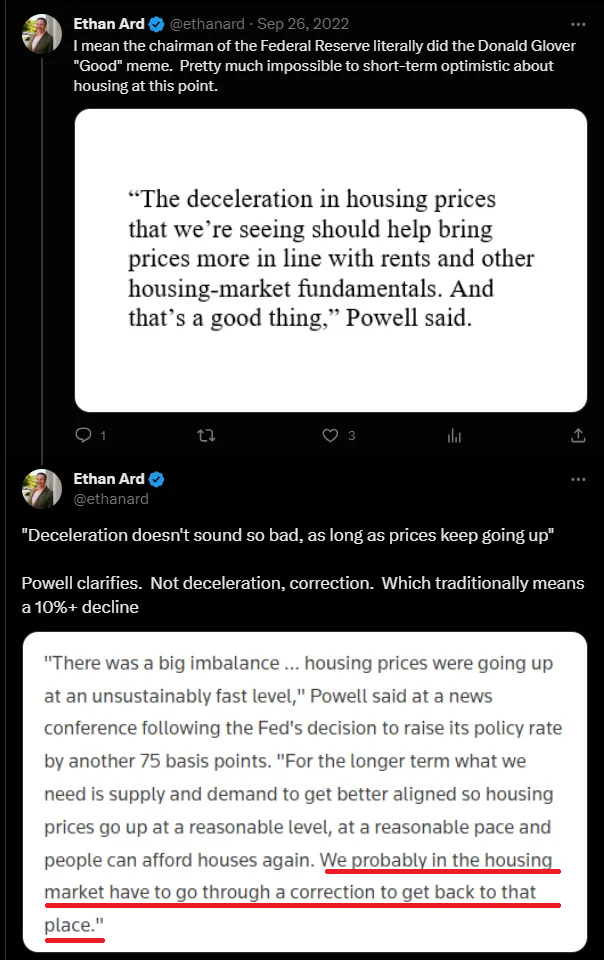

The Fed is not going to bail us out. Jerome Powell has publicly stated that we need a housing price correction.

It’s not that Powell wants real estate to suffer, it’s just that his priority is to drive inflation down. Moreover, he has stated that if prices do go down, that will set the stage for future sustained growth “at a reasonable pace”. It doesn’t matter if we think he is right (though I do). What matters that he believes it, and has stated it in public.

There is almost nothing the Fed prizes more highly than its credibility, so once this is out in the open, it is hard to walk back.

Interesting article and nice data!